I Grew Up Ashamed of Being Asian. Now I'm Learning How to Fully Embrace My Roots

The month of May, Asian Pacific American Heritage Month (AAPIHM), is normally a celebratory time for me. I love taking my daughters to Los Angeles Chinatown and participating in school-organized events at their Mandarin Immersion Elementary school in Venice Beach. In the U.S., the month commemorates the immigration of the first Japanese individual to the U.S. on May 7, 1843, and marks the anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad by mostly Chinese immigrants on May 10, 1869. It's a time to pay tribute to the Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders who have contributed to America's history.

But this year's AAPIHM felt a little different, as I witnessed an increase in hate crimes and violence against my community over the past year. Sadly, between March 19, 2020, and February 28, 2021, 3,800 reports of anti-Asian racist incidents, mostly against women, were received by the Stop AAPI Hate reporting center. I began to fear for the safety of my parents and the mental health of my children. I took more precautions when walking to my car alone at night. In public and at work, I exuded self-assurance, but alone in my room, after my kids went to bed, I cried, unsure of how to ask them if they were okay.

Because of these emotions, I felt compelled to use AAPIHM to share my own experience grappling with an identity that bridges two stories: one that originated in Taiwan and even further back in time, China, and one story that started when my parents immigrated to California and where my life started in a tiny college town in Santa Barbara. The intense clashing of races in this country, with violence directed not just on my own AAPI community but all marginalized communities, forced me to take a step back to actually think about my story as an Asian American.

I was born in Goleta, California, to Taiwanese immigrant parents. I grew up wanting, praying and hoping to blend in; to be as “American” as I could. Full assimilation was my goal and sticking out was avoided at all costs: My parents drilled into me that they had spent their entire lives working toward coming to this country just so I could have a better life, a chance at success and fulfilling my dreams.

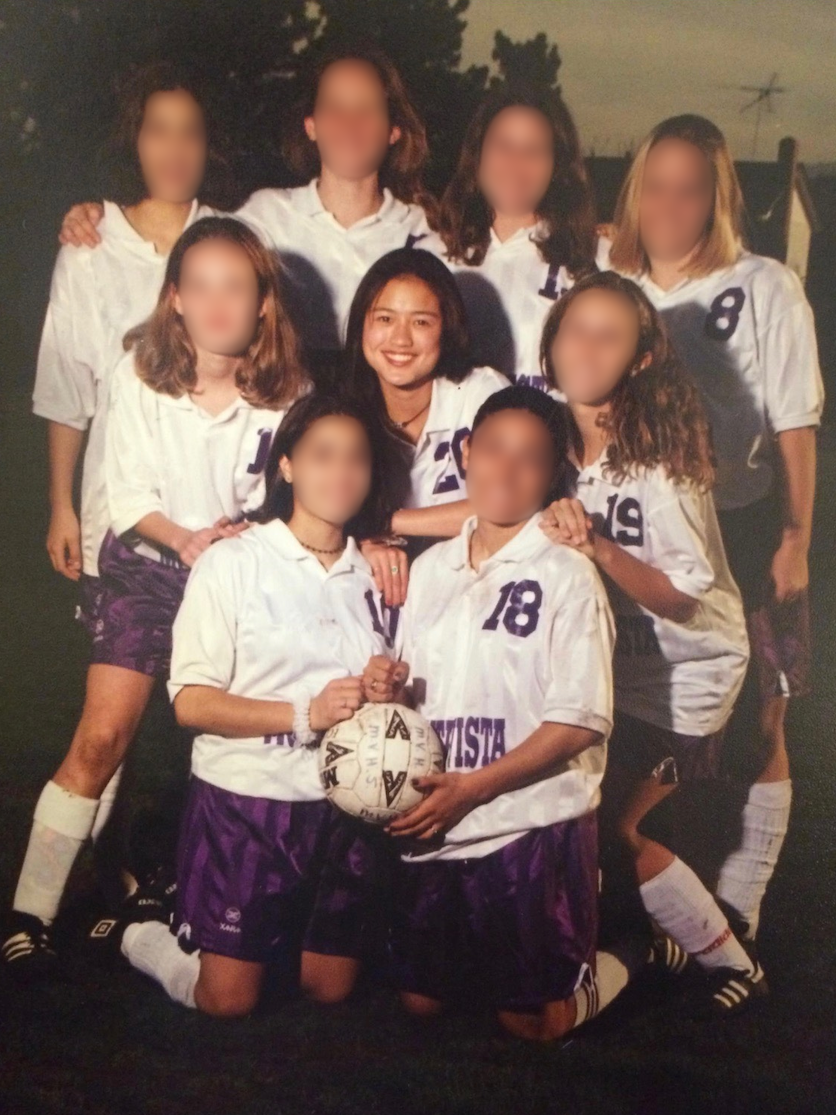

The American Dream was to be my dream, even if I was too young to know what it was or to formulate my own version of it. Ruffle feathers? Better not. Be the best American I could possibly be? Yes ma’am, can do. I lettered in multiple varsity sports, joined every club at school, made sure I did not speak Chinese outside of my home, lectured my own parents to take English lessons and even snuck out of the Chinese school I was forced to attend on Friday nights, dashing my parents’ hopes and dreams I would be fluent in reading and writing Mandarin. My parents were ashamed and disappointed in my actions, and in the ultimate irony, they refused to assimilate into a country they wanted desperately for me to do so flawlessly. Meanwhile, I felt ashamed to be too closely associated with my immigrant roots. If there was this much conflict of identities inside my home, and within myself, how could I possibly manage it in the outside world?

But as I got older, I felt compelled to embrace all parts of myself, including my culture. When I moved away to college, I started to seek out learning about my identity and heritage on my own terms. As a freshman at UCLA, I joined every Asian American club there was, and for the first time in my life, started exploring the complex dynamics of my Asian Americanness. With like-minded company, I began to fully appreciate the delicious array of Chinese foods available in Los Angeles, learned cultural dances, renewed old traditions like Chinese New Year and the Moon Festival and felt pride and confidence to embrace my heritage.

After college I did not have as many Asian friends — I married a white man who had an incredibly accepting and open-minded white family, and I inherited a beautiful white stepdaughter. I introduced them all to facets of my culture, taught them Chinese phrases and traditions, wore a beautiful red qipao (a traditional Chinese formal dress symbolizing beauty and elegance in a color that represents good luck and fortune) at my wedding, played the role of translator for my family members who did not speak English well when our families got together and tried to embrace being the pathway between two cultures. The opposition I felt during my childhood, the pulling of two different origin stories, remained steady in my adult life.

Fast forward to present day, recently divorced but blessed with three beautiful daughters, I am reclaiming my own unique story by returning to my Chinese surname, Wei 魏 – which means “high, lofty, towering,” as a reminder to always keep my head high with elevated self-worth and to carry myself as a tower, strong and proud. Truth be told, I never quite settled into my married name, Warren, because on paper I was no longer Asian American, but an adopted facade of myself. Changing it back feels like coming home to myself — my heritage — regardless of external factors. This deep sense of pride in who I am, what makes me special, a sense of belonging to myself, is something I hope we can all embrace as individuals, regardless of our race.

What I have learned, and continue to learn, is how incredibly lucky I am to come from a diverse and rich lineage. Being American means celebrating individuality and the diverse group of people we have around us. Being Asian American means I have something unique to celebrate with the people I have around me. As novelist Gail Tsukiyama said, “Don’t ever think that just because you do things differently, you’re wrong.” It is these differences that make up our strengths, not our weaknesses.

When I think about my daughters, I am reminded of the term in Chinese 華僑 which translates to “Chinese bridge.” The phrase refers to immigrants like my parents — Chinese people who have settled overseas. Like my parents, I am also a bridge, bringing the hopes and dreams of my parents into the country in which I was born and raised while building another bridge into my children’s futures. My intention for my children is not to impose an exact hope or dream however, but to build the bridge together with them, beam by beam. It is a bridge heading into their unknown, a future with so many pathways into whatever their intentions may be. It is a bridge leading to a safe space for them to carve out their own identities.

My hope for all communities is that through our collective story-telling during AAPIHM and beyond, we realize that our futures are grounded in our legacies, but limitless in their potential. We are all bridges. The opposition I experienced in my childhood and young adult life, perhaps, is present in all of us, regardless of our race or background. Perhaps, it’s part of our American story.

You Might Also Like