Flashback Interview: Radiohead’s ‘OK Computer’ in an Early Computer Age

“It’s not really about computers,” said Radiohead’s Thom Yorke about OK Computer, his band’s brand-new album. He was sitting in a chair, a video camera was pointed at him, and much of what we know about Radiohead hadn’t happened yet.

“It was just the noise that was going on in my head for most of a year and a half of traveling, and computers, and television — and just absorbing it all, really,” said Yorke. “It’s an absorbing record, for good or bad. It’s whatever was around and picking up on it. It’s not really a personal record.”

Some context, please? The year was 1997, the location was West Hollywood’s history-laden Chateau Marmont hotel, and Yorke and Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood were partaking in a video interview aiming to promote OK Computer — out in the States then for perhaps a month and the band’s highest U.S. chart showing yet.

And of course, there would be much more to come: Grammy nominations, Grammy wins, worldwide critical acclaim, massive commercial acceptance, and a pervasive musical influence that helped launch Travis, Coldplay, Elbow, and any other British band favoring acoustic guitars, high-pitched vocals, and artiness you’d care to bring up.

Radiohead mattered, and continue to matter.

They are huge, they are gigantic, and they are exactly the band entitled to celebrate their history via glorious excess. Such excess comes this week with OKNOTOK, a multiformat release commemorating the 20th anniversary of OK Computer and loaded with good stuff: the original album newly remastered, eight B-sides, and three previously unreleased tracks (“I Promise,” “Lift,” “Man of War”) finally seeing official light of day. Boxed set, vinyl, double CD, digital — details here, and it’s a beautiful thing.

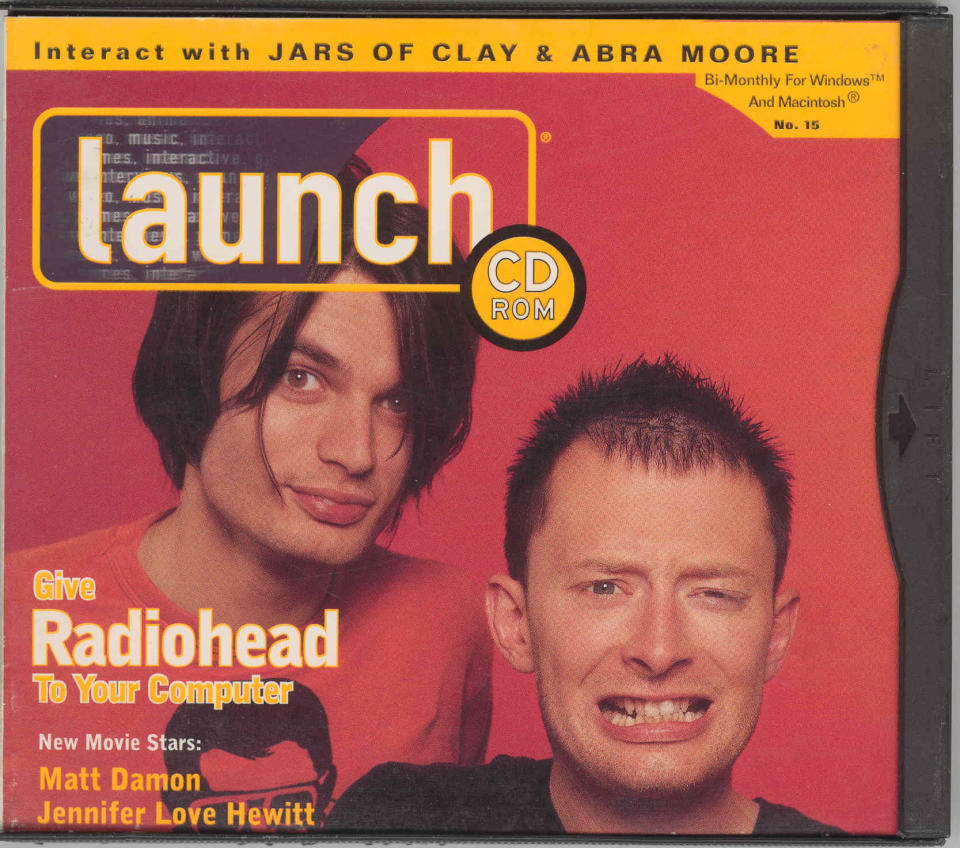

But let’s not forget that this Chateau Marmont ’97 encounter with Radiohead is also having its 20th anniversary — and when examined from that perspective, portions of it now seem oddly fascinating. The band that many now view as wizards of technology, as industry leaders plugged into all that is new and modern, as a cutting-edge combo setting the rules everyone else now follows … were as mystified as any of us about where it all was heading. Which might be one reason they affably took their seats, patiently answered questions about music and (unavoidably) technology, and participated in their first-ever cover story for LAUNCH — a paperless CD-ROM magazine (which later morphed into a website and, eventually, into Yahoo Music) that one consumed via their computer’s CD-ROM drive.

If one had a computer, that is. And if that computer had a CD-ROM drive.

The point? That passages such as the following made perfect contextual sense when asked on that July afternoon in the Chateau Marmont two decades ago.

LAUNCH: How computer-savvy are you two? Do you ever surf the Net?

JONNY GREENWOOD: I’m a big fan of the Internet — well, not a fan, but a big user. Just yesterday, I went to the Voyager site. It has all the music they sent out on Voyager I, the probe they sent out. It’s got “Hello” in 36 different languages recorded on these aluminum discs. I thought that was wild, just amazing. There’s a lot of good stuff out there.

THOM YORKE: I don’t surf the Net at the moment. The reason for that is I had a bit of a freaky incident where someone traced my email address when I first had one two years ago. And I can’t figure out how they found me, because I was using a pseudonym. That really threw me, and I got really paranoid about it.

It’s unclear exactly why people talked about surfing the “Net” rather than the “Web” back then, but so be it. Still, that something so integral to contemporary life in 2017 was then regarded as something that might be avoided when desired — a colorful novelty, a sideshow to the main event — is illuminating.

Yorke went on a bit more, cautioning even then about the inaccuracies the Internet might offer. “I hadn’t even written all of the lyrics yet when we began performing some of these songs,” he said. “And we’d be in the studio with one computer on the Web most of the time. We’d go to the unofficial Radiohead sites and find that people had gone home with these bootlegs of our shows and typed up the lyrics they thought I was singing to our songs. So there I’d be in the studio trying to write my lyrics, and then I’d look on the website to see what other people had written down, what they’d transcribed. That was amazing. It was very odd. I liked that bit of it. That was hilarious.”

To further contextualize, consider at what point Radiohead were in their still-blossoming career: They’d had a huge international hit with their first single “Creep,” then produced a critically acclaimed second album with 1995’s The Bends, which they then promoted in the States while opening for R.E.M. and Alanis Morissette — enviable slots, both. And as for making the follow-up?

“I think there was a general atmosphere, especially in the press, that we were all set up to do ‘the big third crossover album,’ with the pop radio song that would cross us over into something enormous,” Greenwood said. “But it sort of feels like we’ve just made a record for the people who were into the last one, really.”

However, soon after its release, OK Computer was heralded as the album of the year. Did Radiohead really not know what they had when it was completed?

“When we finished it and were putting it together,” Yorke said then, “I was pretty convinced that we’d sort of blown it. But I was kind of happy about that, because we’d gotten a real kick out of making the record. Now, in terms of people saying it’s ‘the album of the year’ — people say that all the time. In Britain, it’s great: In the space of two weeks, our album was the album of the year, and so was Prodigy’s. Two weeks from now it will be another album. It’s just what people say.”

Actually, two weeks from then, the LAUNCH crew would shuttle over to Washington, D.C.’s 9:30 Club and capture Radiohead’s performance of the OK Computer track “Lucky” during a soundcheck.

But none of us in that room knew that then. Just as no one knew that the LAUNCH CD-ROM containing Radiohead’s performance and interview would be virtually unplayable in 2017 after 20 years of software and hardware evolution. Or that OKNOTOK would be out in 20 years’ time celebrating OK Computer’s original release. Funny how that works.

Anyway, much has been made of the band’s taking a deliberate turn toward the arty side of things at this point in their career — and that isn’t far from the truth. OK Computer drew its artistic inspiration, if not its actual sound, from sources pop fans of the era might not have expected. Including jazz and avant-garde classical music.

“It isn’t pumped full of singles,” noted Yorke, “but then The Bends wasn’t either, or at least that’s what people said. I don’t think it’s uncommercial, in the sense that if we’d set out to make an uncommercial record, we could have done a much better job. I think it has an atmosphere. We had a sound in our heads that we had to get onto tape, and that’s an atmosphere that’s perhaps a bit shocking when you first hear it, but only as shocking as the atmosphere on Pet Sounds. But then, the sort of things we were listening to were so removed from all that anyway.”

Who were they listening to?

“We weren’t really listening to any bands at all — it was all, like, Miles Davis and Ennio Morricone and composers like [Krzysztof] Penderecki, which is sort of atmospheric, atonal weird stuff. We weren’t listening to any pop music at all. But not because we hated pop music — because what we were doing was pop music. We just didn’t want to be reminded of the fact.

“Bitches Brew by Miles Davis was the starting point of how things should sound; it’s got this incredibly dense and terrifying sound to it. That’s what I was trying to get — that sound — that was the sound in my head. The only other place I’d heard it was on a Morricone record. I’d never heard it in pop music. I didn’t hear it there. It wasn’t there. It wasn’t like we were being snobs or anything; it was just like, ‘This is saying the same stuff we want to say.’”

In retrospect, what may have signaled the start of Radiohead fully embracing their Radioheadness may have been their crucial decision to record most of OK Computer on their own, as a co-production with good friend and engineer Nigel Godrich, in a very unlikely location. That would be St. Catherine’s Court, a mansion near Bath owned by actress Jane Seymour and by no means an industry hub.

“We were all of the same age, mid-to late 20s, and doing a record in the middle of nowhere,” said Greenwood. “And there were no established professionals there. It wasn’t a real recording studio, and we had our friend doing the artwork in the studio at the same time. We were all at the same stage of our life and all working together for something. It was quite a buzz.”

Added Yorke: “We didn’t want to be in the studio with A&R men coming around, nice air conditioning, staring at the same walls and the same microphones. That was madness. We wanted to get to another state of mind — one that we understood and could deal with.”

If it was an experiment, it could not have been more successful: The album reached the top of the U.K. charts, was compared to no less than Sgt. Peppers by at least one enthusiastic press outlet, sold by the boatload, and set the aesthetic tone for what has become one of the most fascinating and unparalleled careers in the music business.

Still, as Radiohead sat in their Chateau Marmont chairs back in ’97, they yet again had to answer questions about “Creep” — their first single, the song that started it all for them, and a success that conspicuously overshadowed much of their other early work. It was an issue for them even then.

When a song becomes that popular, they are asked, does it become a millstone for you? Do you wish you never had to play it again?

“It’s not a millstone now,” Yorke said. “It’s a good song. Ultimately, you know, if you have a song that moves people in that way, you can’t possibly disclaim it or moan about it, because that’s why you’re in this business. That’s why we’re in this business. It’s a pop record.

“It’s not a millstone anymore because it moved people at the time. And what else could you ask for?”

Give us 20 years, Thom, and we’ll get back to you on that.